Biologics and The Battle For Sight: How A New Wave of Therapies is Transforming Graves’ Orbitopathy Treatment

Nov 14, 2025

Table of Contents

From steroid dependence to molecular precision, the Graves’ orbitopathy treatment is undergoing a seismic shift. But can innovation keep pace with the burden of disease?

From Desperation to Discovery

For decades, Graves’ orbitopathy stood as one of medicine’s most frustrating autoimmune disorders. The condition, triggered by misguided immune attacks on the tissues around the eyes, left patients with a cruel spectrum of symptoms — bulging eyes, double vision, chronic pain, and, in some cases, permanent loss of sight.

Downloads

Click Here To Get the Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Treatment Market: A Billion-Dollar Opportunity For Pharma Companies

- Late-Stage Thyroid Eye Disease Treatments: 4 Prominent Therapies to Consider

- Graves’ Disease Treatment Revolution: What’s Next in Line?

- Thyroid Eye Disease: The Hidden Impact of Thyroid Dysfunction on Eye Health

- Tepezza receives approval; a new way to treat Alzheimer’s

Physicians had few tools. High-dose corticosteroids were the default weapon, able to dampen inflammation but notorious for their bluntness: they often failed to halt disease progression and left behind metabolic wreckage. Radiotherapy was inconsistent. Surgery, including orbital decompression, strabismus correction, and eyelid procedures, remained a fallback, but was invasive and imperfect.

For patients, the experience was often a long and grueling ordeal. Treatment alleviated symptoms but rarely addressed the underlying cause. Many lived with lasting disfigurement or visual disability.

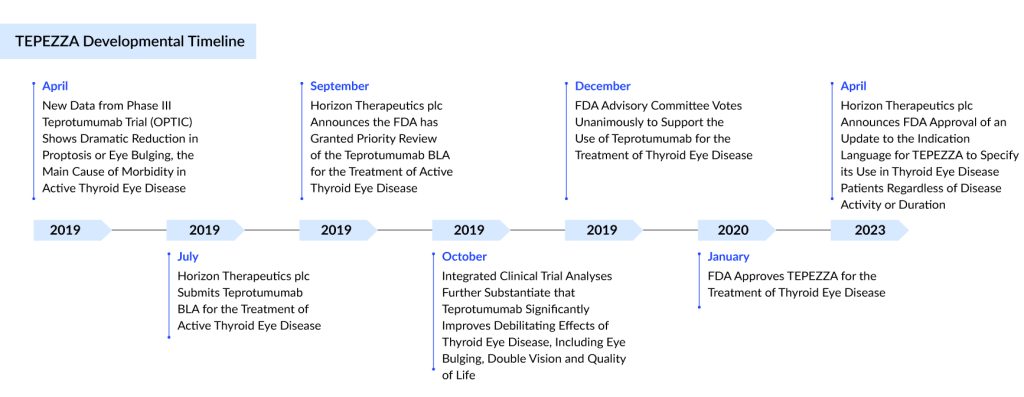

Then came 2020. With the US FDA’s approval of TEPEZZA (Teprotumumab), the first targeted biologic for Graves’ orbitopathy, the narrative changed. Here was a drug designed not to manage the fallout but to strike at the molecular machinery of the disease itself. It was hailed as a revolution.

The Scale of the Graves’ Orbitopathy Burden

Understanding why this shift matters requires a hard look at the numbers. Graves’ orbitopathy is not a rare curiosity. In the United States alone, there were approximately 610,000 diagnosed Graves’ orbitopathy prevalent cases in 2024, a number projected to climb in the coming years. Women account for nearly four in five cases, reflecting the autoimmune bias toward female biology.

The chronic form of the disease dominates the landscape. In 2024, more than 440,000 Americans were living with chronic Graves’ orbitopathy, compared to about 170,000 with acute disease. That matters because chronic disease is where treatments often falter — once the inflammatory blaze cools, fibrotic scarring remains, leaving patients with enduring functional and cosmetic issues.

Behind every statistic is a human toll: patients struggling with impaired vision, altered appearance, psychological distress, and disrupted careers. The economic cost, while harder to quantify, is profound — lost productivity, high healthcare utilization, and, increasingly, the price of advanced therapies.

“Behind every case number lies a face changed, a career interrupted, a life reshaped.”

TEPEZZA (Teprotumumab): Breakthrough or Mirage?

Teprotumumab arrived with extraordinary promise. A monoclonal antibody targeting the Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor (IGF-1R), it was the first therapy to interrupt the pathogenic cascade driving Graves’ orbitopathy directly.

In clinical trials, the results stunned even seasoned ophthalmologists. Patients experienced rapid reductions in proptosis, in some cases rivalling those achieved with orbital decompression surgery. Diplopia improved, inflammation subsided, and quality-of-life scores rose dramatically.

For the first time, medicine seemed to offer not just palliation but genuine disease modification.

Yet, as with all breakthroughs, reality has proven more complicated

- Durability of benefit: Not all patients maintain long-term responses. Relapses and incomplete responses remain challenges.

- Safety concerns: Adverse events such as hearing impairment and hyperglycemia are nontrivial and may limit use in certain populations.

- Access and affordability: In the US, a full treatment course costs more than USD 300,000, sparking payer resistance and excluding many patients from access. Even in markets where regulatory approval has been obtained, such as the EU, UK, and Japan, restrictive reimbursement policies threaten to blunt the impact.

Teprotumumab is undeniably a milestone, but it is not the end of the journey. If anything, it has spotlighted both the potential and the limitations of biologics in this disease.

The Chronic Disease Approval: A Game-Changer

Originally approved only for active disease, Teprotumumab received an additional US approval in 2023 for the treatment of chronic Graves’ orbitopathy. This was a watershed moment. For the first time, patients with chronic, inactive disease — often marked by fibrotic changes traditionally seen as unresponsive to systemic therapy — gained access to a targeted medical option.

This approval also reshaped the competitive pipeline. Agents like Veligrotug (VRDN-001) and other IGF-1R inhibitors were already positioning themselves in chronic disease, but Teprotumumab’s label expansion raised the bar. Now, pipeline Graves’ orbitopathy drugs must not only match Teprotumumab’s efficacy but also demonstrate advantages in durability, safety, or convenience.

Subcutaneous TEPEZZA: Chasing Convenience

Another frontier is delivery. Teprotumumab is currently available only as an intravenous infusion, which limits accessibility and adds cost. Horizon Therapeutics, the developer, is conducting a subcutaneous trial of Teprotumumab aimed at offering the same efficacy with a more patient-friendly administration route.

If successful, this could address two of the drug’s biggest criticisms, inconvenience and payer pushback, while further solidifying its market dominance. However, it also intensifies competition: pipeline agents like VRDN-003, which are also subcutaneous, will have to carve out their niche in a space where convenience no longer serves as a straightforward differentiator.

Graves’ Orbitopathy Treatment: The Pipeline of Hope

The arrival of Teprotumumab has catalyzed a wave of innovation. The Graves’ orbitopathy clinical trial pipeline is no longer a trickle; it is a race.

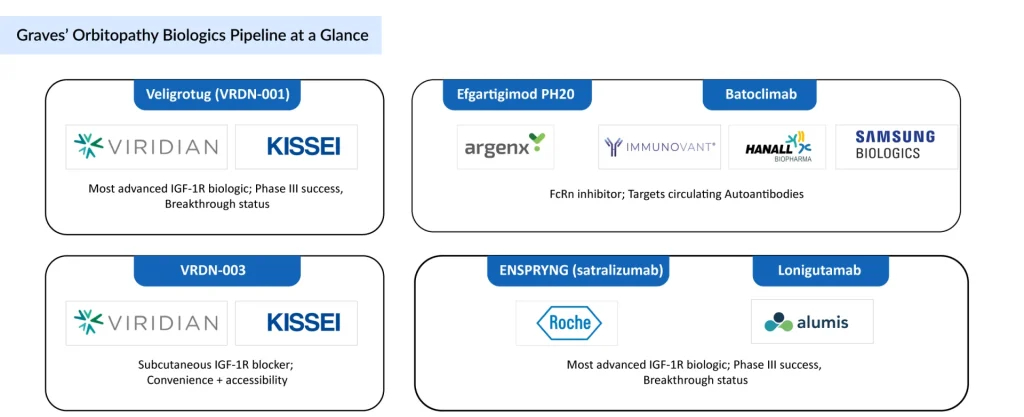

Next-generation IGF-1R Blockade

Veligrotug (VRDN-001), an intravenous IGF-1R antagonist, is emerging as a formidable challenger. Phase III results from the THRIVE program demonstrated robust efficacy in both active and chronic disease. In chronic patients, long neglected by clinical trials, proptosis reduction was sustained through a full year. That durability matters. In 2025, the FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation, accelerating timelines toward a likely 2026 launch.

VRDN-003, a subcutaneous formulation, promises even greater convenience. Moving biologics into the outpatient setting could expand accessibility and reduce costs.

Alternative Biological Pathways

FcRn inhibitors, such as Efgartigimod PH20, aim to reduce circulating autoantibodies—a strategy with precedent in other autoimmune conditions. Batoclimab, Satralizumab (ENSPRYNG), and Lonigutamab represent further mechanistic bets, each probing a different node in the autoimmune cascade.

The common thread is ambition: to broaden efficacy, tackle chronic disease, and move toward Graves’ orbitopathy therapies that are more effective, safer, and easier to deliver.

“The question is no longer whether biologics work — it is which biologic works best, for whom, and at what stage.”

Established Biologics Already in Use

While much of the excitement lies in the Graves’ orbitopathy drug pipeline, some biologics are already being used in practice, albeit off-label. Rituximab, a B-cell-depleting therapy, and Tocilizumab, an IL-6R blocker, have been tested in patients resistant to corticosteroids. Their results have been mixed, and neither drug has achieved the transformative impact of Teprotumumab. Still, for patients with limited options, they represent meaningful alternatives — a reminder that clinicians are already turning to biologics in the fight against this disease, even beyond approved therapies.

Redrawing the Treatment Map

What does this wave of biologics mean for day-to-day practice? It is nothing short of a paradigm shift.

- Steroids on borrowed time: While still first-line globally due to cost and familiarity, corticosteroids are increasingly being questioned. Their side-effect profile, limited durability, and inability to alter disease course are glaring weaknesses in the biologic era.

- Surgery redefined: Orbital decompression, once a near inevitability for disfiguring proptosis, may become less common as biologics deliver surgical-level reductions noninvasively. For patients, this could mean fewer scars, fewer risks, and fewer operations.

- Chronic disease finally addressed: Perhaps the most exciting frontier is the chronic, fibrotic stage of Graves’ orbitopathy. Historically, once fibrosis set in, medical therapy was futile. Now, with biologics like Veligrotug showing efficacy in chronic disease, that dogma may crumble.

If validated, this would be a profound shift — not only relieving acute inflammation but also altering the long-term trajectory of the disease.

The Challenges Ahead in Graves’ Orbitopathy Treatment

For all the optimism, hurdles remain

- Affordability and access: Teprotumumab’s six-figure price tag set a precedent that few healthcare systems can sustain. Without pricing innovation, even the most effective drugs will fail to reach most patients.

- Physician adoption: Outside the US, biologics remain less familiar in ophthalmology and endocrinology. Confidence will grow, but it will take time.

- Safety signals: Any long-term biologic therapy must balance efficacy and immunological risk. Post-marketing surveillance will be crucial.

The risk is that biologics create a two-tier world: innovation for the few, traditional steroids and surgery for the many.

Conclusion: Biology, not Steroids, Will Write the Future

Teprotumumab cracked open a door that had been shut for decades. The next wave of biologics, from Veligrotug to FcRn inhibitors, is pushing it wider. For patients, the promise is immense: therapies that are more precise, more durable, and perhaps capable of rewriting the natural history of a once intractable disease.

Yet optimism must be tempered with realism. Prices remain prohibitive, access is uneven, and long-term outcomes are not fully known. Graves’ orbitopathy is entering its biologic era — but whether this becomes a true renaissance will depend as much on health policy and pricing reform as on science.

“The coming decade will determine whether Graves’ orbitopathy remains a story of incremental progress — or becomes a showcase of how biologics can transform an autoimmune disease once thought untouchable.”

Downloads

Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- Thyroid Eye Disease: The Hidden Impact of Thyroid Dysfunction on Eye Health

- Late-Stage Thyroid Eye Disease Treatments: 4 Prominent Therapies to Consider

- Tepezza receives approval; a new way to treat Alzheimer’s

- Graves’ Disease Treatment Revolution: What’s Next in Line?

- Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Treatment Market: A Billion-Dollar Opportunity For Pharma Companies