Towards a Promising Future: Unveiling Advancements in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria (CSU) Treatment

Jul 01, 2025

Table of Contents

Chronic urticaria is a persistent skin condition marked by recurrent, itchy wheals or hives that last for more than six weeks and can persist for over a year. As per DelveInsight’s analysts, approximately 4.7 million prevalent cases of chronic urticaria were reported across the 7MM in 2024, underscoring a significant disease burden. Based on the classification of urticaria, it can be broadly divided into chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), where the cause is unknown, and chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU), which is triggered by specific stimuli. Understanding the types of chronic urticaria is crucial for accurate diagnosis and the selection of appropriate urticaria treatment strategies. While CSU treatment often involves antihistamines and advanced biologics, chronic inducible urticaria treatment typically focuses on identifying and avoiding known triggers, in line with evolving urticaria treatment.

What is Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria?

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), also referred to as chronic idiopathic urticaria, is a debilitating form of CSU skin disease characterized by the spontaneous activation of mast cells and basophils, which release pro-inflammatory mediators that trigger urticaria symptoms. Key features include persistent itching, hives, and in some cases, angioedema, lasting longer than six weeks. The hallmark presentation involves red, itchy, swollen lesions or “wheals”, which may vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters and often merge to form larger patches. As one of the more severe types of chronic urticaria, CSU significantly impacts quality of life, with patients experiencing up to 30% reduced job performance, in addition to considerable direct and indirect healthcare costs. Given its burden, chronic spontaneous urticaria treatment remains a clinical priority, with evolving urticaria treatment guidelines 2024 focusing on symptom control, long-term management, and improving patient well-being.

Downloads

Click Here To Get the Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- Mapping the Top Asthma Therapies: Inhaled Blockbusters and Injectable Powerhouses

- Sanifit nets USD 80.9 M; FDA approves Dupixent for CRS; AbbVie buys Allergan

- Can Dupixent Be A Gamechanger In The Atopic Dermatitis Treatment Landscape?

- Sandoz’s Generic Revlimid; Agios’ Pyrukynd; Organon Announces 4Q & Full-year Earnings ...

- DUPIXENT Receives First-Ever Biologic Approval for COPD: Adds Another Jewel in its Crown

Diagnosing the Itch: Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

Chronic spontaneous urticaria disproportionately affects women, who are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed. Most patients develop symptoms between 20 and 40 years of age, with spontaneous urticaria presenting as recurring hives and/or angioedema without a known trigger. Diagnosing CSU involves a detailed medical history, physical examination, and, in some cases, additional tests such as blood work, allergy testing, or skin biopsies to rule out other urticaria causes like allergic reactions or infections.

Diagnostic tools such as the Urticaria Activity Score (UAS), Urticaria Control Test (UCT), Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life questionnaire, and Urticaria Severity Score (USS) are essential for assessing disease activity and treatment response. The autologous serum skin test (ASST) is often used in CSU to detect auto-reactivity, a hallmark of the disease. In some cases, autoantibodies against IgE or its high-affinity receptor (FcεRI) are implicated, confirming the autoimmune nature of CSU in certain patients. This complexity underlines the importance of personalized diagnostic approaches in chronic spontaneous urticaria treatment.

Current Approaches to Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Treatment

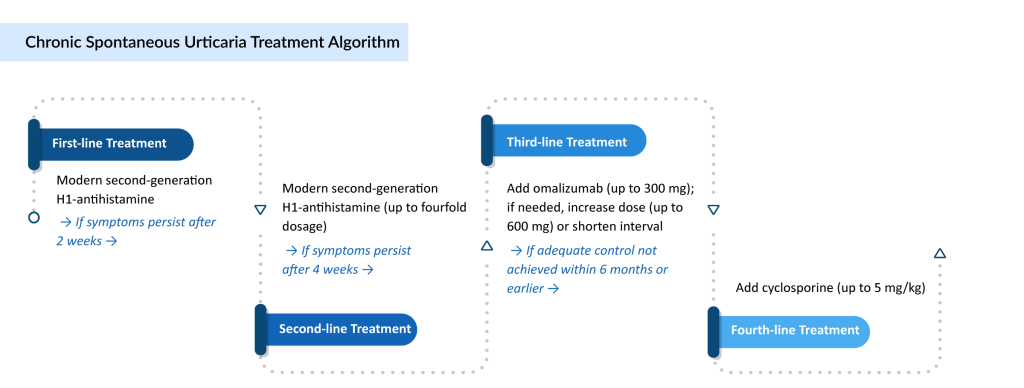

Chronic spontaneous urticaria treatment is often complex, requiring a personalized and stepwise approach to control symptoms and reduce flare-ups. The typical CSU treatment algorithm begins with second-generation H1-antihistamines as the first-line therapy, given their ability to block histamine receptors and alleviate common symptoms like itching, redness, and swelling.

For patients unresponsive to standard doses, up-dosing of second-generation H1-antihistamines up to fourfold is recommended as the second step. If symptoms persist, XOLAIR (omalizumab), a monoclonal antibody and the only currently approved targeted therapy for CSU, is used as the third-line treatment. However, around one-third of patients remain symptomatic despite omalizumab.

In such refractory cases, cyclosporine may be considered, especially for individuals with severe disease not responding to any antihistamine dose or biologic therapy. Beyond this, a range of off-label chronic urticaria treatments, including corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, antidepressants, leukotriene receptor antagonists, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, IV immunoglobulins, interferon, phototherapy, and plasmapheresis, can be explored based on individual case needs and treatment response.

Notably, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) still includes first-generation H1-antihistamines in its treatment pathway, whereas most global practices recommend avoiding them due to sedation and side effects, highlighting variations in treatment strategies across regions.

Advancements in the Field of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Treatment Space

Over the past few decades, substantial progress has been made in the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). Evolving scientific insights, updated classifications, and evidence-based guidelines have contributed to more precise disease management. Below are the major milestones and improvements shaping the current CSU landscape:

- Improved Disease Understanding

Research has deepened our grasp of CSU’s underlying biology, highlighting roles for mast cells, basophils, autoimmune responses, and mediators like IgG anti-FcεRIα, alongside toll-like receptors and coagulation pathways. - Updated Classification of Urticaria

Modern classification distinguishes chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) from chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU), which includes forms like cholinergic, aquagenic, and contact urticaria. The outdated terms “chronic idiopathic” and “physical urticaria” have been refined to reflect clearer mechanistic and trigger-based distinctions. - Development of Diagnostic & Monitoring Tools

Both prospective and retrospective tools are now used to assess symptom severity and quality of life:- UAS7: Tracks daily wheals and itching over 7 days.

- UCT, USS, and CU-Q2oL: Evaluate disease control and impact retrospectively.

- Refined Clinical Guidelines & Treatment Algorithms

International guidelines (e.g., EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO) promote a step-wise CSU treatment pathway:- First-line: Second-generation H1-antihistamines.

- Second-line: Up-dosing up to fourfold.

- Third-line: Omalizumab for antihistamine-refractory cases.

- Fourth-line: Cyclosporine in severe, resistant CSU.

- Regional Divergence in Guidelines

The AAAAI still includes first-generation antihistamines, in contrast to most global bodies that discourage their use due to sedative effects. - Evidence-Based Practice with GRADE Methodologies

Newer guidelines now integrate GRADE frameworks, helping standardize diagnosis, optimize CSU treatment, and guide clinical decision-making. - Ongoing Gaps

Despite progress, the field still lacks validated biomarkers to fully explain pathogenesis or predict chronic spontaneous urticaria treatment response.

Unfolding Emerging Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Treatment Options

Despite a structured, guideline-based ladder approach to chronic spontaneous urticaria treatment, a significant proportion of patients—nearly one-third—remain symptomatic even after using omalizumab, the only currently approved biologic. Conventional therapies like second-generation H1-antihistamines and omalizumab often fail to achieve complete symptom control, particularly in patients experiencing severe itching, wheals, and angioedema. These limitations highlight a persistent unmet need and fuel the development of upcoming chronic spontaneous urticaria drugs that promise better efficacy and novel mechanisms of action.These investigational therapies are primarily targeted toward refractory CSU, aiming to go beyond symptom relief and restore long-term disease control. Several agents now in late-stage development offer hope to patients who are unresponsive to current treatments and signal a shift toward precision medicine in urticaria care.

Pipeline Highlights: Leading Upcoming Drugs in CSU

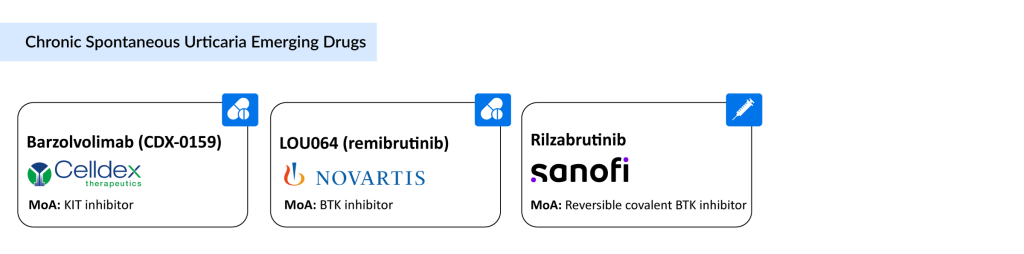

- Barzolvolimab (CDX-0159) – Celldex Therapeutics

A novel KIT inhibitor, barzolvolimab is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the KIT receptor tyrosine kinase, which regulates mast cell survival and activity, key in CSU pathology.- As one of the most promising upcoming CSU drugs, it demonstrated strong disease control and quality-of-life improvements in Phase II trials.

- Key updates were shared at the AAAAI 2025 Annual Meeting, and in May 2025, long-term 76-week data were accepted for a late-breaking oral presentation at EAACI 2025.

- Currently being evaluated in Phase III, barzolvolimab could emerge as a viable alternative for omalizumab-resistant patients.

- Remibrutinib (LOU064) – Novartis

Among the most anticipated upcoming chronic spontaneous urticaria drugs, remibrutinib is a highly selective Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) inhibitor that blocks histamine release and mast cell degranulation.- In the pivotal REMIX-1 and REMIX-2 Phase III trials, it met all primary endpoints and demonstrated rapid, durable symptom relief through Week 52 in patients unresponsive to antihistamines.

- Novartis presented compelling efficacy and quality-of-life data at the 2025 AAAAI/WAO and AAD meetings.

- Regulatory filings are planned for early 2025, with FDA approval anticipated in the second half of 2025. Pediatric trials are also ongoing.

Challenges Despite Pipeline Progress

While these upcoming CSU drugs hold promise, most are still being developed as add-on or rescue therapies, rather than first-line curative options. Additionally, they still require robust long-term safety and efficacy data to support regulatory approvals and widespread adoption.

There are also notable gaps in the broader CSU landscape:

- Limited epidemiological data, especially among children and adolescents

- Poor differentiation between CSU and chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU) in many clinical studies

- A lack of validated biomarkers to accurately diagnose and predict treatment response

Market Outlook

According to DelveInsight’s analysis, the chronic spontaneous urticaria market size in the 7MM (US, EU5, Japan) was approximately USD 2 billion in 2024. Driven by the launch of these upcoming chronic spontaneous urticaria therapies, along with improved diagnosis and rising awareness, the market is projected to grow significantly over the forecast period (2025–2034).

FAQs

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a type of chronic urticaria that occurs without a clear external trigger. It typically lasts more than six weeks and can persist for over a year. As a long-term inflammatory skin condition, it significantly affects quality of life and is often associated with psychiatric comorbidities. The condition falls under the broader urticaria classification, which also includes chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU), triggered by physical stimuli.

The exact cause of CSU is not fully understood, but it is often linked to autoimmune responses, where autoantibodies activate mast cells and basophils, leading to hives and swelling. Other factors like stress, infections, and medications may worsen the condition. As opposed to acute urticaria, which is usually allergic, CSU is more complex and persistent.

Diagnosis is mostly clinical, based on symptom duration and the presence of hives or angioedema. Doctors may conduct blood tests, thyroid screening, and allergy tests to rule out other causes. Tools like the autologous serum skin test (ASST) and basophil histamine release assay help identify autoimmunity in CSU.

CSU treatment follows a stepwise approach, starting with second-generation H1-antihistamines. If symptoms persist, the dose may be increased up to fourfold. For patients unresponsive to antihistamines, omalizumab is recommended as a third-line option. In severe or refractory cases, csu treatments may include cyclosporine or other off-label immunomodulatory.

Downloads

Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- The Evolving Landscape of COPD Treatments: New Hope for Patients

- Sandoz’s Generic Revlimid; Agios’ Pyrukynd; Organon Announces 4Q & Full-year Earnings ...

- Major Highlights and Insights from the AAAAI Annual Meeting, 2024

- How Emerging Pipeline Therapies Will Unfold the Severe Asthma Treatment Market Dynamics?

- Can Dupixent Be A Gamechanger In The Atopic Dermatitis Treatment Landscape?