Social Determinants of Health and their Impact on COVID-19

Jul 31, 2025

Table of Contents

As the healthcare landscape moves away from fee-for-service models and toward value-based care, understanding the social determinants of health (SDOH) has become crucial. These non-medical factors—ranging from economic stability and education to neighborhood conditions and social support—are now recognized as powerful predictors of health outcomes. According to the World Health Organization, social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, as well as the broader systems and policies that shape daily life. These factors go beyond the clinical setting, highlighting how poverty, housing insecurity, food deserts, and lack of transportation can directly affect a person’s ability to stay healthy.

In fact, research has shown that health and illness follow a social gradient, where individuals in lower socioeconomic positions tend to experience worse health outcomes. With growing awareness of health inequities—especially during public health crises like COVID-19—healthcare organizations, governments, and payers are increasingly integrating SDOH data into their decision-making. Understanding what are the social determinants of health, recognizing examples of SDOH, and implementing interventions based on these insights can drive better outcomes and promote health equity across populations.

Downloads

Click Here To Get the Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- Merck, Dewpoint’s HIV Pipeline; Pfizer, BioNTech ‘s COVID-19 Vaccines; Roche’s Tecent...

- Bristol Myers’ Opdivo combo Opdualag for Melanoma; Biogen’s Aduhelm; Marinus’ Ztalmy for CDKL-5 D...

- Contract Organizations Impacting Pharma Development and Manufacturing

- Cerner, Scanwell Health and Personal Genome Diagnostics Acquisition; Zynex’s Fluid Monitori...

- Novel coronavirus crumbles down as soon as it lands on copper

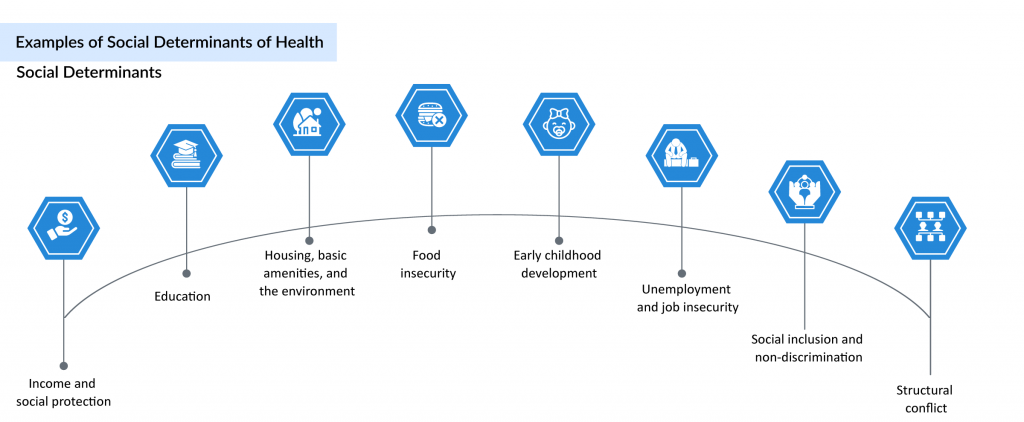

What are the Different Types of Social Determinants of Health?

Social determinants of health may be more influential than healthcare access or individual lifestyle choices in shaping overall health. Numerous studies suggest that social determinants of health account for 30% to 55% of health outcomes, highlighting their critical role in public health. In fact, the contribution of non-health sectors often exceeds that of the healthcare sector in determining population health outcomes. Addressing SDOH is essential to improving overall well-being and reducing long-standing health inequities, and it requires coordinated action from all sectors and civil society. As a key subset of the broader health determinants, SDOH intersect with factors such as:

Why are Social Determinants of Health Important?

Achieving meaningful health equity requires a comprehensive understanding of the social determinants of health (SDOH)—the non-medical factors that shape health outcomes across a person’s life. These include the environments in which individuals live and work, their level of education, income security, and the social structures surrounding them. Deep-rooted challenges such as poverty, systemic racism, stigma, and unequal access to healthcare continue to create significant disparities in health. While clinical interventions remain vital, health systems, educational institutions, and policy-makers are increasingly urged to address the underlying determinants of health, rather than focusing solely on individual behavior or biological risk factors.

Evidence shows that when people are supported with essential SDOH examples—such as affordable housing, safe neighborhoods, clean air, nutritious food, and equitable education—their overall well-being improves, and reliance on expensive healthcare services decreases. This shift in focus, from reactive treatment to proactive structural change, strengthens the foundation for equitable health outcomes. A strong social determinants of health model promotes coordinated action across all levels of governance and public health infrastructure. By addressing the full list of social determinants of health, from economic stability to community support, healthcare systems can help foster societies that prioritize not just physical health, but also emotional, social, and cultural resilience.

Social Determinants of Health Screening Tools

A growing body of evidence confirms that improving health outcomes depends not just on medical care, but on addressing the broader social determinants of health (SDOH)—non-clinical factors that shape health at every stage of life. Achieving health equity means ensuring that every individual has the chance to reach their full health potential, regardless of socioeconomic status or structural barriers. Systemic challenges such as poverty, limited access to care, inadequate education, stigma, and racism continue to drive disparities. To overcome these, health systems, educational institutions, and community organizations are being encouraged to look beyond individual choices and actively address the underlying determinants of health.

When individuals have reliable access to food, toxin-free environments, education, stable jobs, and supportive housing, key examples of SDOH, their overall health improves, while the need for costly healthcare interventions declines. At all levels of governance, focusing on the impact of social determinants of health can lay the foundation for a society that prioritizes not only physical wellness but also emotional and cultural well-being.

To support this shift, many Transforming Complex Care sites have adopted or developed structured SDOH assessment tools to better identify patients’ social needs and barriers to care. Among the most widely used screening methods is the PRAPARE tool, developed by the National Association of Community Health Centers. It includes 15 core and 5 optional questions and is designed to capture a patient’s social risks and strengths, with structured data that can be integrated directly into electronic health records.

Another resource, part of the American Academy of Family Physicians’ EveryONE Project, offers short- and long-form social determinants of health screening tools in English and Spanish, which can be administered by staff or completed by patients themselves. Meanwhile, the AHC-HRSN screening tool—created by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, consists of 10 questions targeting health-related social needs and is intended to be self-administered.

As health systems increasingly recognize the importance of these social health determinants, integrating reliable screening tools and addressing root causes remain essential steps toward reducing disparities and building equitable, community-based care models.

Social Determinants of Health and COVID-19

The social determinants of health (SDOH), such as economic status, living conditions, race or ethnicity, played a defining role in shaping the trajectory and outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Vulnerable populations, particularly those living in poverty or experiencing homelessness, faced heightened risks of infection due to overcrowded living conditions, limited access to testing, and reduced ability to follow public health guidelines like physical distancing. For many, the ability to isolate or work remotely was not a viable option—highlighting how social inequalities can exacerbate both short- and long-term morbidity. In addition, school closures intensified food insecurity among low-income children, disrupting vital nutrition sources like school meal programs and increasing susceptibility to illness due to malnutrition.

As the pandemic unfolded, disparities in COVID-19 morbidity were further magnified by pre-existing chronic conditions such as asthma—conditions closely tied to structural determinants of health, including poor air quality, inadequate housing, and limited access to care. Factors like cigarette exposure, race or ethnicity, and economic instability showed an additive effect on vulnerability to severe illness. In many minority communities, where residents disproportionately serve as essential workers, have limited health insurance, and rely heavily on public transit, the pandemic exposed deep-rooted inequities. The impact of social determinants of health was not just visible but glaring, serving as a wake-up call to researchers, healthcare providers, and policymakers.

The interconnected nature of the five domains of social determinants of health, education access, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, economic stability, and social and community context—became particularly evident during COVID-19. For instance, an individual’s level of education often dictated job opportunities, which influenced income level, access to health coverage, and ultimately, neighborhood safety and quality of social support networks. These interconnected factors directly influenced not only exposure risk but also recovery outcomes during the pandemic.

Although the concept of health determinants is well-established, the pandemic has accelerated its relevance across the healthcare value chain. Today, there is renewed urgency to integrate SDOH screening tools and assessments into care delivery models. As stakeholders increasingly look for sustainable approaches to population health, social determinants of health examples provide a common language for researchers, legislators, and community leaders to collaborate on interventions. The COVID-19 crisis underscored the importance of embedding social health determinants into national health strategies to ensure equitable, contextualized, and resilient care for all communities.

Role of Pharma in Addressing Social Determinants of Health

COVID-19 underscored how social determinants of health (SDOH)—like poverty, housing instability, and food insecurity—can exacerbate health risks and create barriers to care, particularly among underserved populations who faced higher infection rates and worse outcomes. In light of this, pharmaceutical companies, which once primarily addressed SDOH through charitable foundations, are now taking more proactive steps. These include forging direct partnerships with provider groups and payers, as well as expanding efforts to diversify clinical trials. Such shifts reflect a growing industry-wide recognition that improving health equity requires deeper, more coordinated engagement beyond traditional healthcare delivery.

Pharmaceutical companies are increasingly recognizing the critical role of social determinants of health (SDOH) in shaping patient outcomes and are evolving from passive contributors to active collaborators in addressing health inequities. While the COVID-19 pandemic amplified disparities, it also accelerated industry-wide efforts to engage more deeply with underserved communities. By focusing on SDOH, companies aim to improve patient access, adherence, and overall health outcomes. Notably, organizations such as CVS pharmacy, Blue Cross of North Carolina, and OneCity Health have spearheaded partnerships to tackle issues like transportation and food insecurity. Major pharmaceutical players, including Pfizer, Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche, have joined forces to advance health equity initiatives. These shifts signal the growing potential for the pharmaceutical sector to play a transformative role in addressing SDOH and positively impacting the populations it serves.

What Lies Ahead?

What lies ahead is a broader and more systemic integration of social determinants of health (SDOH) into the core of healthcare and pharmaceutical strategies. While the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the devastating effects of ignoring SDOH—particularly on impoverished and overcrowded communities—it also served as a turning point, pushing stakeholders to acknowledge that pandemics are as much social issues as they are medical crises. Moving forward, reducing global disease burdens requires interdisciplinary collaboration among healthcare professionals, public health experts, sociologists, anthropologists, researchers, governments, and organizations like the NIH, CDC, and WHO. Together, they can identify and address the structural causes of health disparities.

Pharmaceutical companies, in particular, are uniquely positioned to act, as SDOH impacts every stage of a product’s lifecycle—from research and development to market maturity. By proactively identifying social risk factors and unmet community needs, pharma companies can help close the gap in health equity. The future demands more than clinical innovation—it calls for sustained investment in education, outreach, and social infrastructure that empower vulnerable populations and reshape the way healthcare systems view and deliver care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Social determinants of health refer to non-medical factors—such as socioeconomic status, housing, education, neighborhood environment, and social context—that shape people’s health. In the context of COVID-19, these factors influenced who was more likely to be exposed, infected, or suffer worse outcomes, often magnifying health inequities.

Key factors include economic instability (e.g. job loss, low income), crowded or unstable housing, limited access to transportation or healthcare, food insecurity, and poor living conditions. These created conditions where social distancing, testing access, and isolation were harder to sustain, increasing COVID-19 transmission and worse health outcomes.

Healthcare systems began using structured screening tools—like PRAPARE and AHC-HRSN—to identify social risk factors (e.g. housing, food needs, transportation) in patients. By integrating these tools into electronic health records, providers could better understand non-clinical barriers patients faced and tailor support.

Pharma began shifting from traditional philanthropic efforts to direct engagement, such as partnering with providers and payers to address barriers like access or diversity in clinical trials. This reflects growing recognition that health equity must go beyond drugs and include social interventions.

The pandemic highlighted the need for systemic integration of social determinants into healthcare planning and decision-making. To reduce health disparities, policies must address root causes (poverty, housing, education), clinical and social care must be better coordinated, and cross-sector partnerships must be strengthened.

Downloads

Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- GSK’s Covifenz; Idorsia’s Quviviq; GSK’s ZEJULA; EMA Expands its Nod for BMS, Eli Lilly, an...

- CereVasc’s eShunt System Study; FDA Approves NGS-Based CDx for Trastuzumab Deruxtecan; Nanopath S...

- GE and Medtronic’s Collaboration; Vivalink’s Multi-Vital Blood Pressure Patch; Foldax...

- Contract Organizations Impacting Pharma Development and Manufacturing

- Keeping a track on COVID-19 through Wearable Technology