Epilepsy Monitoring Devices: Transforming Patient Care and Seizure Management

Dec 03, 2025

Table of Contents

Epilepsy affects nearly 50 million people globally, making it one of the most common neurological disorders, with about 80% of cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries where diagnostic and treatment resources are limited. Yet with timely and appropriate care, up to 70% of individuals with epilepsy can become seizure-free, underscoring the transformative impact of accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. According to DelveInsight’s estimates, in 2023, there were approximately 7 million prevalent cases of epilepsy in the 7MM. Of these, the US accounted for 48% of the cases.

Central to improving outcomes is effective monitoring, which provides essential clinical insight into seizure type, frequency, and triggers. Monitoring supports accurate diagnosis, guides treatment decisions, whether medication adjustments, surgical evaluation, or neuromodulation, and helps prevent misdiagnosis, ineffective therapies, and avoidable complications.

Downloads

Click Here To Get the Article in PDF

Categories of Epilepsy Monitoring Devices

Epilepsy monitoring tools form a spectrum from gold-standard laboratory EEGs through ambulatory systems and wearables to implantable devices. The choice of technology depends on the clinical question, setting (clinic, emergency room, home), and resource availability.

Conventional (in-lab) EEG Systems

Conventional EEGs are conducted in specialized laboratories using multiple scalp electrodes, typically 19 to 32 or more, positioned according to standardized systems such as the 10–20 electrode placement method. These studies may be short, routine recordings lasting 20–60 minutes, or extended video-EEG monitoring sessions in an epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) spanning several days to weeks, synchronizing continuous EEG with video to capture clinical events. EMUs are considered the gold standard for defining seizure characteristics and localizing onset zones because of their extensive spatial sampling and high-quality video correlation. Prolonged monitoring also significantly increases the likelihood of recording spontaneous seizures, which is essential for evaluating candidates for epilepsy surgery. However, EMUs are highly resource-intensive, requiring dedicated inpatient beds, specialized technologists, and experienced neurologists to interpret large volumes of data. As a result, access remains limited in many parts of the world, a significant concern given the substantial treatment gaps identified by the WHO in low- and middle-income countries.

Ambulatory EEG Systems

Ambulatory EEG (AEEG) systems are portable scalp-EEG recorders that enable patients to be monitored in their home environment for 24–72 hours or longer, providing extended recording with far less infrastructure than an inpatient EMU. They offer a higher likelihood of capturing events compared with short routine EEGs because patients are observed during their normal daily activities, making them especially useful when episodes are infrequent. AEEG is also more cost-effective and widely accessible than EMU-based monitoring. However, the absence of continuous video can make clinical–electrical correlation less precise, and issues such as electrode displacement and motion-related artifacts are more common in home settings, thereby reducing overall data quality.

Wearable Seizure-detection Devices

Wearable seizure-detection devices, including wristbands, smartwatches, headbands, and adhesive patches, use combinations of sensors such as accelerometers, photoplethysmography for heart rate, electrodermal activity sensors, and occasionally limited EEG leads to identify physiological patterns associated with seizures, particularly convulsive events. They enable continuous, non-invasive monitoring during daily activities. They can alert caregivers or clinicians when a seizure-like episode occurs, supporting patient safety, tracking seizure frequency, and monitoring treatment response. However, most commercially available wearables are optimized for detecting generalized tonic–clonic seizures and are less sensitive to focal or non-motor events. Challenges remain regarding false positives caused by movement or exercise and false negatives for subtle seizures. Additionally, regulatory clearance varies by device and indication, and these technologies are generally not designed to replace EEG-based diagnostic methods.

Implantable EEG Devices

Implantable epilepsy monitoring devices are placed either intracranially, such as subdural grids, strips, or depth electrodes, or subcutaneously, allowing continuous recording of brain activity. Some systems focus solely on long-term intracranial EEG monitoring, while others combine sensing with therapeutic stimulation, as seen in responsive neurostimulation technologies. These devices offer exceptional signal fidelity and precise localization, providing insight into seizure onset zones that scalp EEG cannot capture. Closed-loop implantable systems can detect abnormal electrical activity in real time and deliver targeted stimulation to interrupt or reduce seizures. However, because implantation requires invasive neurosurgical procedures, these devices carry risks such as infection and demand highly specialized, multidisciplinary care teams. Their cost and limited availability also restrict use, making them most appropriate for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy or those undergoing evaluation for epilepsy surgery.

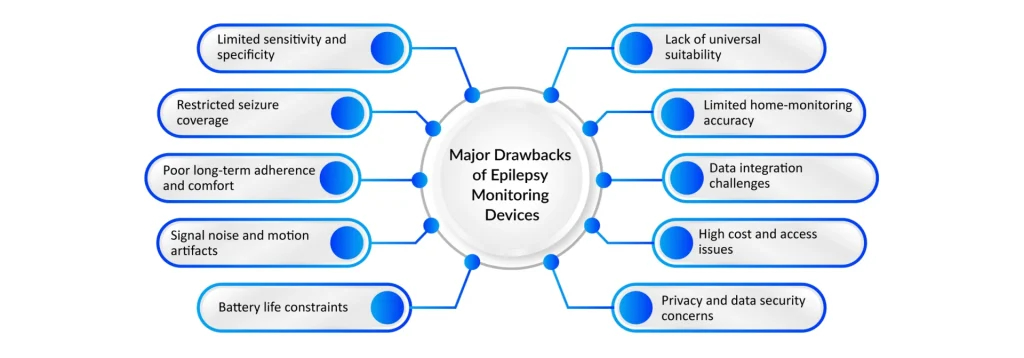

Current Limitations of Epilepsy Monitoring Devices

Despite major advances, epilepsy monitoring still faces several enduring challenges. Diagnostic access and the global epilepsy treatment gap remain the most significant barriers, as the WHO reports that many people, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, lack access to proper diagnosis and essential medicines, limiting the real-world impact of even the most advanced monitoring tools. Technology-related issues persist as well, including limitations in sensitivity versus specificity: wearables may detect convulsive seizures but miss subtle or focal events. At the same time, high-density or intracranial EEG provides richer data but is impractical for everyday, long-term use.

Additionally, prolonged recordings generate massive data volumes that require expert interpretation, making the process time-consuming and costly, and automated systems remain imperfect at handling artifacts and variability. Patient comfort and adherence also influence monitoring quality; traditional EEG setups can be cumbersome and disruptive, while even user-friendly wearables bring concerns around privacy, battery life, and false alarms. Finally, cost and infrastructure constraints pose major obstacles. Advanced EMUs and implantable devices demand specialized resources, and CDC data show that even in high-income countries like the U.S., millions of individuals with epilepsy face barriers in accessing specialty care, highlighting the ongoing need for more equitable and scalable monitoring solutions.

Clinical Applications of Epilepsy Monitoring Devices Across Healthcare Settings

Primary care, community clinics, outpatient neurology services, and hospital-based epilepsy programs each play a distinct yet interconnected role in epilepsy monitoring. At the frontline, primary care and community clinics focus on early identification and referral, using brief EEGs when available, structured clinical checklists, and WHO-supported community education under initiatives such as mhGAP. With proper training, many cases of epilepsy can be accurately diagnosed and managed at this level, significantly narrowing the epilepsy treatment gap in underserved regions. Once referred, outpatient neurology clinics provide diagnostic confirmation and ongoing management through routine EEGs, ambulatory EEG systems, and increasingly, wearable devices that allow continuous seizure tracking. These tools support medication adjustments, help document seizure frequency and triggers, and improve the precision of long-term care.

More complex cases require advanced monitoring environments. Epilepsy Monitoring Units (EMUs) employ prolonged video-EEG, intracranial EEG when needed, and multimodal neuroimaging (MRI, PET) to map seizure onset zones and determine suitability for surgical or neuromodulatory interventions. In emergency and acute care settings, rapid EEG systems and portable diagnostic tools are critical for quickly identifying non-convulsive status epilepticus, especially when clinical signs are subtle, enabling timely, lifesaving interventions. For ongoing real-world assessment and home and long-term monitoring, solutions such as wearables, ambulatory EEGs, and integrated seizure diaries provide continuous safety oversight and long-duration seizure tracking. These tools are particularly beneficial for individuals with nocturnal seizures or elevated injury risk, providing valuable insights that enhance treatment precision and patient safety across the continuum of care.

Epilepsy Monitoring Devices: Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The future of epilepsy monitoring is moving toward technologies that deliver clearer signals, smarter analytics, and greater global accessibility. Multimodal sensing and hybrid devices are at the forefront of this evolution, blending EEG with cardiac, motion, and autonomic measurements to enhance detection accuracy. By integrating surface EEG with accelerometry and heart-rate variability, these systems outperform traditional single-sensor wearables, especially for generalized convulsive seizures.

At the same time, implantable closed-loop neuromodulation is reshaping treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy. Responsive neurostimulation devices that detect abnormal intracranial activity and deliver targeted stimulation have already demonstrated reductions in seizure frequency. Advances in device miniaturization, battery life, and long-duration recording capabilities will likely broaden their applicability and patient acceptance in the coming decade.

Parallel advancements in AI and cloud-based analytics are transforming how clinicians interpret large EEG datasets. Machine learning models can accelerate seizure detection, minimize false positives, and automate triage by flagging suspicious EEG segments for expert review. Still, robust validation across populations, seizure types, and clinical environments remains vital to ensure reliability and safety. Researchers are also developing long-term, minimally invasive EEG systems, such as subcutaneous electrode arrays, which offer months of continuous recording without the invasiveness of intracranial electrodes.

Complementing these innovations, the rise of telemedicine and distributed monitoring has expanded access to specialist care by enabling remote EEG review and real-time consultations—an approach strengthened during the COVID era and aligned with global public health strategies. Ultimately, democratizing access will be the defining measure of success. WHO initiatives show that empowering primary healthcare providers through training and integrating epilepsy care into routine services can significantly narrow the treatment gap. Combined with affordable, scalable monitoring solutions, these models ensure that technological progress translates into real-world improvements for patients worldwide.

Downloads

Article in PDF